Celia Dropkin

(1887 – 1956)

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

Yiddish writer Celia Dropkin both shocked and delighted New York literary society of the 1920s and 1930s with her poetic depictions.

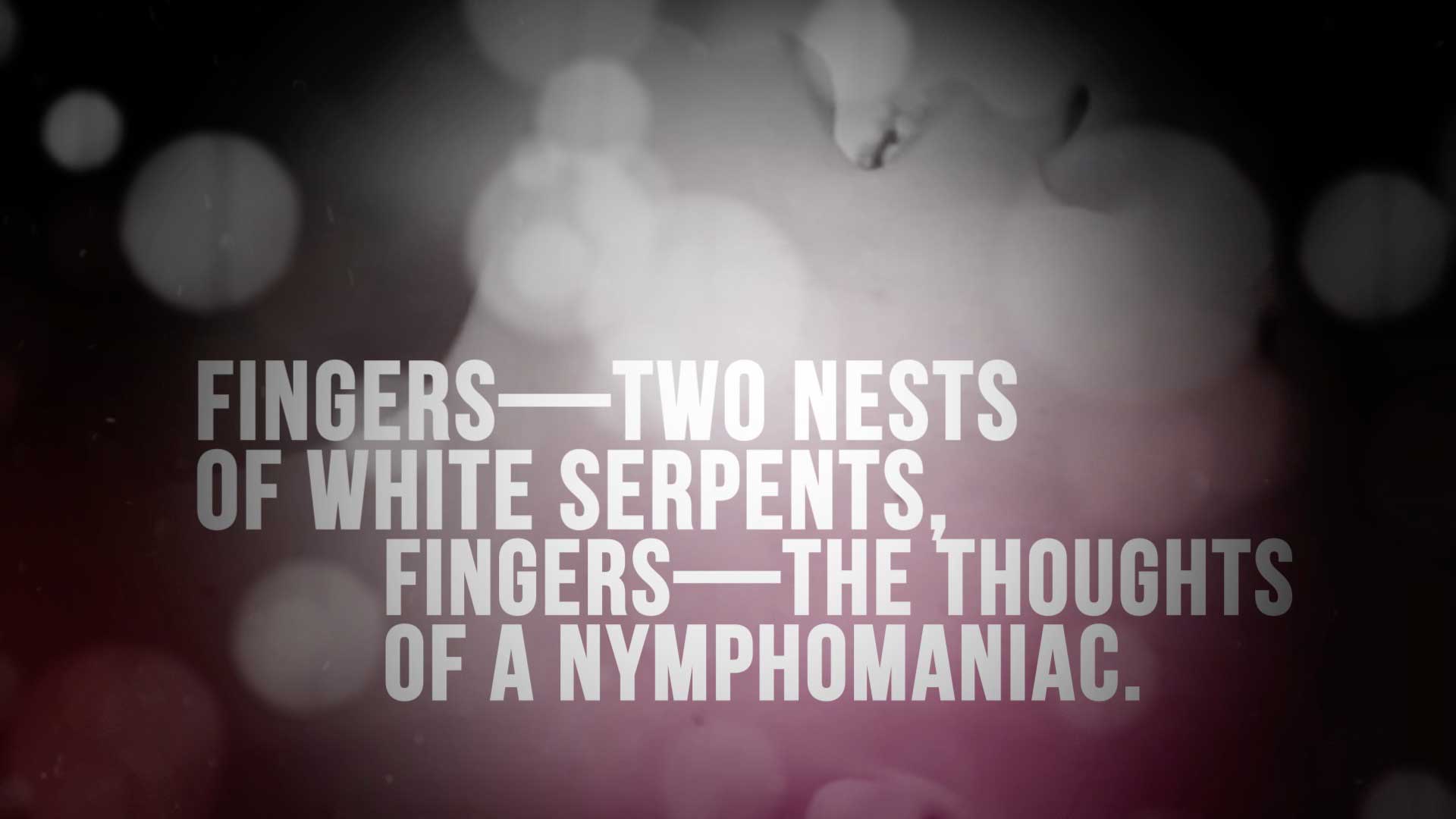

The explicitly sexual imagery and themes of Celia Dropkin’s poems redefined the ways modern Yiddish poetry could depict relationships between women and men.

The explicitly sexual imagery and themes of Celia Dropkin’s poems redefined the ways modern Yiddish poetry could depict relationships between women and men.Dropkin’s poems, with their anger and passion, call into question societal assumptions about love.

Even her poems about depression, about mother love, and about nature are infused with erotic energy. Best known for her poetry, Dropkin also published short stories and was an accomplished visual artist.

READ MORE:

Dropkin is fierce and uncompromising, immediate and compelling, a radical thinker about women, the body, the conditions of love. She is disgusting. She is intimidating. She is open, and cruel, and cruelest to herself. She is in love with the idea of love, yet certain that love is always fraught, contingent, and humiliating.

Dropkin is fierce and uncompromising, immediate and compelling, a radical thinker about women, the body, the conditions of love. She is disgusting. She is intimidating. She is open, and cruel, and cruelest to herself. She is in love with the idea of love, yet certain that love is always fraught, contingent, and humiliating.READ MORE:

Born of exile and Diaspora, Yiddish, since about the 10th century, had been a vernacular of the people. A fusion of several languages (Germanic, Slavic & Romance languages – elements of Hebrew and Aramaic) created by Ashkenazi Jews, it was standardized only about a hundred years ago, influenced by the “classic” writers of modern Yiddish literature: Mendele, Peretz and Sholem Aleichem.

Dropkin and other modernist women poets reshaped this domestic village patois into writing in which the female self could speak. She was no longer on her knees scrubbing floors and asking God to get pregnant. She was a woman expressing desire.

READ MORE:

Celia Dropkin was born Tsilye Levine in Bobruisk present-day Belarus on December 5, 1887. She had a traditional early secular education and then completed the Russian gymnasium.

She headed to Kiev for further study and was mentored by the Hebrew writer Uri Nissan Gnessin (1881–1913), who encouraged her writing. Celia formed a passionate friendship with Gnessin, but he prevented it from becoming a romance because he had tuberculosis.

After returning home and marrying Samuel (Shmaye) Dropkin in 1909, the young couple was forced to emigrate because of her husband’s Bundist activism. In New York, she continued writing and in 1918 began publishing her first Yiddish poems to great acclaim.

READ MORE:

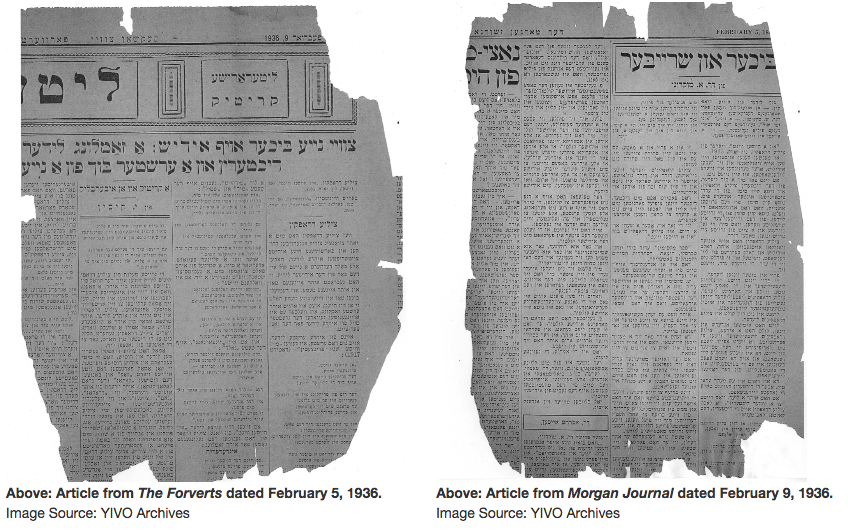

A volume of Dropkin’s poems–titled In Heysn Vint—was published in 1935. Male critics, especially the literary critic, Shmuel Niger, criticized Dropkin’s poetry for being too personal. [1] An article from Morgn Journal, shown below, describes Dropkin’s poetry as “Goyish.” Not all of the reviews were as negative, however. Below, a review from The Forverts, dated February 5, 1936, refers to Dropkin as a “nayem kol,” or “new voice.”

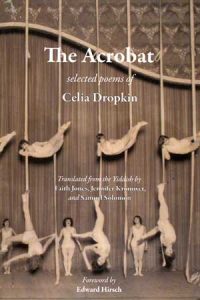

Dropkin died on August 18, 1956 from cancer and was buried at Mount Lebanon Cemetery. Following her death, her poetry continued to be translated. In 1994, with the guidance of her granddaughter Francis Dropkin, A French translation of selected poems–titled “Dans le vent chaud”–was published. In 2014, Faith Jones, Jennifer Kronovet, and Samuel Solomon translated selected poems into English.

READ MORE:

She wrote first in Russian but turned to Yiddish on arrival in New York, where she participated in the already active Yiddish poetry world, including the experimental In-Zikh (Introspectivist) poets.

These poets rejected the socialist concerns of the “sweatshop poets,” who portrayed the working conditions of Eastern European immigrants, and instead, focused on individual experience. They brought Yiddish poetry into the 20th century.

Introspectivist Manifesto

“The world exists and we are a part of it. But for us, the world exists only as it is mirrored in us, as it touches us […]the art of expressing feelings and perceptions adequately.”

Celia developed more markedly transgressive themes than theirs: sexuality, depression, guilt & longing, fury, violence, even the representation of sado-masochism & other taboo, once hidden subjects.

The Red Flower

Rebellion and Guilt in the Poetry of Celia Dropkin

– Sheva Zuker

– Sheva Zuker

In addition to the shockingly open eroticism of Dropkin’s poems, one is also struck by their almost total lack of Jewishness.

On the contrary, (some of her) poems are flagrantly unJewish. The usual themes of Women’s Jewish poetry – pious ancestors, Sabbath candles, love of Israel and the Jewish people, God – are absent from Dropkin’s poetry. Was this a conscious rebellion against Jewish tradition or simply a reflection of the limited role religion and Jewishness in general played in her life? The extent of her Jewishness was, according to (her son) John, “just Yiddish”.

READ MORE:

Like songs, Dropkin’s poems are terse and musical and carefully constructed to explode with maximum impact. They reveal the relationships between women and men in a way that was unprecedented in Yiddish literature. They feel utterly contemporary, which is why we are just now catching up with her.

In the poem “Zoyg oys” or “Suck,” she turns, somewhat provocatively for a Jewish poet, to Christian iconography, merging the crucifixion of Jesus with sadomasochistic sex:

Hammer my hands,

nail my feet to a cross:

burn me, be burned,

take all my ardor

and leave me deeply ashamed:

suck it from me and throw it away,

become estranged, alienated

and go your own way.

The few who bothered to review In heysn vint (In the Hot Wind), mostly criticized her erotic sensibility, her outpouring of feeling, the idea that “even her illusions can’t get away from her body— her body won’t let up.”

It’s true that Dropkin writes out of a woman’s body. She enters poetry as a forthright lover, a subversive agent of love, not an object of desire, a passive beloved.

For one, Dropkin helped prove that Yiddish — long regarded as provincial, folkish — could serve as a medium for serious art.

Dropkin’s contemporaries and predecessors tended to see Yiddish women’s poetry as second-class: “a lesser form in a lesser language.” Dropkin helped change that perception.

Above all, Celia Dropkin’s was a world of contradictions and dual identities. Like so many women, she saw herself as both a mother and a sexual being. In both cases, Dropkin was torn between two identities. But they also humanize Dropkin and her contemporaries, speaking to the conflicts that humans everywhere face. This, perhaps, is why her poetry feels so relevant today.

READ MORE:

Celia Dropkin is having a bit of a moment. Her poems have been popping up in hip literary journals. And now comes Dropkin’s Selected Poems, with an introduction by Edward Hirsch. The three translators of The Acrobat, Faith Jones, Jennifer Kronovet, and Samuel Solomon, note in a brief essay included in the book that they have “felt [Dropkin’s] presence” in their readings in European and American modern and contemporary, in writers as diverse as Walt Whitman and Jean Valentine. In these gorgeous translations, Dropkin fits easily into the American poetic idiom. She is a brilliant watcher of nature and equally adept at urban pastoral.

“New York at Night by the Banks of the Hudson”

“Seeping from the cells of your skyscrapers / in golden honey—light / through millions of windows”

READ MORE:

Rather softer (then the boldness and honesty of her poetic imagery) are the images Dropkin created with her paintbrush.

In exploring our Dropkinalia, we came across a rare item in our Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library: a collection of Dropkin’s little-known watercolor and oil paintings.

“One would often find her on 57th Street, en route to the art school, with a heavy bundle of her canvases and other painter’s tools. Exhausted, she shlepped herself along on her ailing, lame foot (the result of a sickness), weary but cheerful and revived—she had discovered in herself a new artistic talent!”

READ MORE: